When a pregnant person takes a medication, it doesn’t stay in their body alone. That drug can cross the placenta and reach the developing fetus-sometimes in surprising amounts. For decades, many assumed the placenta acted like a shield, protecting the baby from harmful substances. But that’s not true. The placenta is more like a smart gatekeeper: it lets some things through, blocks others, and sometimes even pushes drugs back out. Understanding how this works isn’t just academic-it directly affects whether a baby is born healthy or faces serious risks.

The Placenta Isn’t a Wall-It’s a Filter

The placenta weighs about half a kilogram and has a surface area larger than a small bedroom. It’s packed with blood vessels from both mother and baby, separated by just a thin layer of tissue. This isn’t a solid barrier. It’s designed for exchange: oxygen in, carbon dioxide out, nutrients flowing to the baby, waste flowing back. But drugs? They slip through too-depending on their size, chemistry, and the stage of pregnancy.

Small molecules under 500 daltons pass easily. Think nicotine (162 Da), alcohol (46 Da), or caffeine. They don’t need special help. They just diffuse across, like water through a sieve. Larger molecules-like insulin at over 5,800 daltons-barely make it. Only about 0.1% of the mother’s insulin reaches the fetus. That’s why insulin injections are safe during pregnancy: the baby doesn’t get enough to cause harm.

But size isn’t everything. Lipid solubility matters too. Drugs that dissolve in fat (like many antidepressants and seizure meds) slip through cell membranes more easily. A drug with a log P value above 2 has a 50-60% higher chance of crossing. Ionization plays a role too. If a drug is charged at the body’s pH (around 7.4), it gets stuck. Only the uncharged version can pass. That’s why some medications barely cross, even if they’re small.

Active Transport: The Placenta Pushes Back

The placenta doesn’t just sit there and let drugs in. It has built-in pumps-called transporters-that actively kick drugs back into the mother’s bloodstream. Two of the most important are P-glycoprotein (P-gp) and breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP). These are the body’s security guards for the fetus.

Take HIV medications. Lopinavir, a protease inhibitor, only reaches about 60% of the mother’s concentration in the baby’s blood. Why? Because P-gp is shoving it back. When researchers blocked P-gp in lab models, lopinavir levels in the fetus jumped by 70%. Same with saquinavir and indinavir. Without those pumps, fetal exposure could be dangerously high.

Even more interesting: some drugs interfere with these pumps. Methadone and buprenorphine, used to treat opioid use disorder in pregnancy, can block BCRP. That means they might let other drugs-like chemotherapy agents-pass through more easily. In lab tests, methadone cut paclitaxel’s transport barrier by nearly 20%. That’s not just theoretical. It could change how we treat cancer in pregnant people.

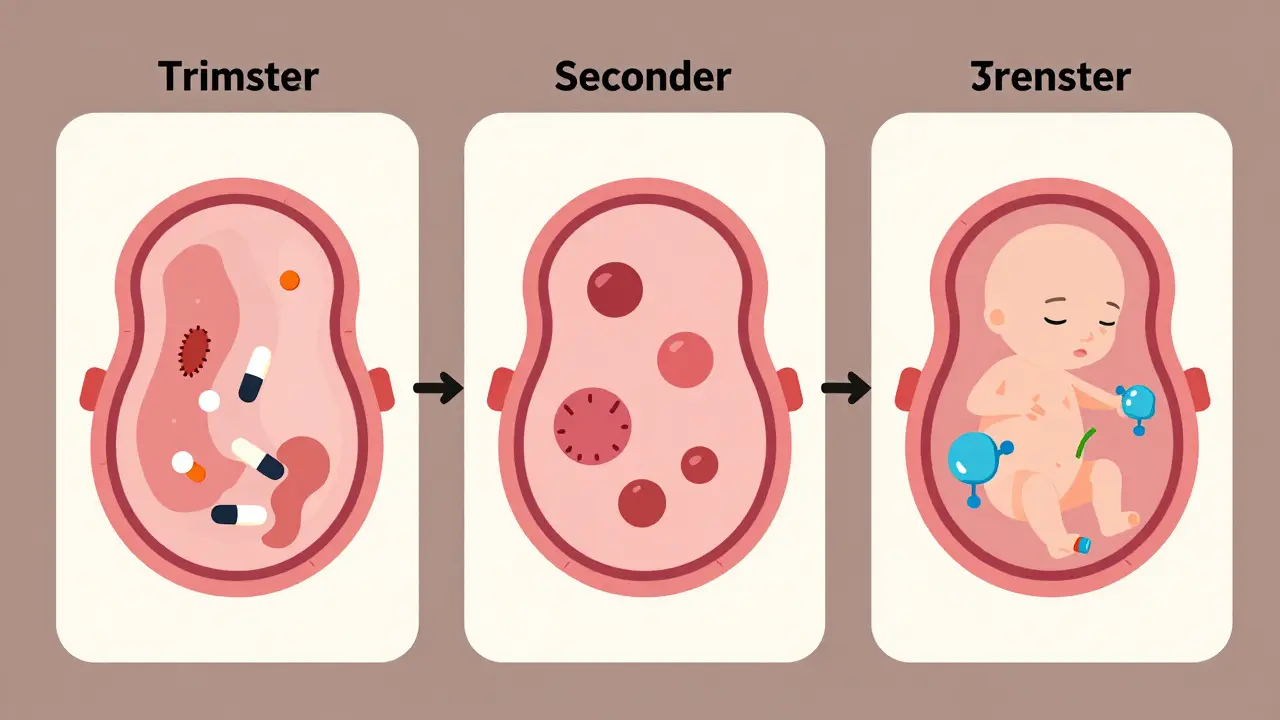

First Trimester: The Most Dangerous Time

Many assume the later stages of pregnancy are riskiest. But the opposite is true. In the first trimester, the placenta is still developing. The protective pumps like P-gp and BCRP aren’t fully active yet. Tight junctions between placental cells are looser. That means more drugs get through.

Studies show the placenta is 2-3 times more permeable to small, lipid-soluble drugs in early pregnancy than at term. That’s why exposure to thalidomide between weeks 4 and 8 caused devastating limb deformities. The drug slipped through easily. The fetus was undergoing critical organ formation. By week 12, the placenta had tightened up. The same dose later wouldn’t have caused the same damage.

This is why doctors urge extreme caution with any medication in the first 12 weeks. Even something as common as ibuprofen, which is usually fine later, can interfere with fetal heart and kidney development if taken early. The window for harm is narrow-but wide enough to cause lifelong consequences.

Real-World Examples: What Crosses, and What Happens

Some medications cross easily-and we know exactly what happens next.

SSRIs like sertraline reach near-equal levels in the baby’s blood as in the mother’s. About 30% of babies exposed to these drugs in late pregnancy show temporary symptoms: jitteriness, trouble feeding, breathing issues. These usually fade within days. But the long-term effects? Still being studied.

Opioids like methadone and buprenorphine cross with 65-75% efficiency. That’s why 60-80% of babies born to mothers on these drugs develop neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS). They go through withdrawal after birth-trembling, crying nonstop, having seizures. It’s treatable, but it’s preventable with better planning.

Valproic acid, used for epilepsy and bipolar disorder, crosses almost completely. And it’s dangerous. Babies exposed to it have a 10-11% chance of major birth defects-cleft palate, heart problems, neural tube defects. That’s 3-5 times higher than the general population. Many doctors now avoid it entirely in pregnancy.

Digoxin, used for heart rhythm problems, is an exception. It crosses the placenta, but it’s not affected by P-gp blockers like verapamil. That’s why it’s still used safely in pregnancy-doctors know exactly how it behaves.

What’s Missing: The Gaps in Our Knowledge

Here’s the hard truth: we don’t know how most medications affect the fetus. The FDA says 45% of prescription drugs lack enough data to say whether they’re safe in pregnancy. Why? Because we can’t ethically test drugs on pregnant women. Most studies use animals-but mouse placentas are structurally different. They’re 3-4 times more permeable. A drug that seems safe in mice might be deadly in humans.

Even worse, most research uses placentas from full-term births. But the most sensitive development happens early. We’re trying to understand a moving target with outdated tools.

That’s why new technologies are so important. Placenta-on-a-chip devices now mimic the real organ’s flow and transport. Researchers can test drugs in real time, with human cells, without harming a baby. One model predicted glyburide transfer within 1% of actual human tissue results. That’s a breakthrough.

Non-invasive imaging is helping too. Using radioactive tracers, scientists can now watch how a drug moves from mother to fetus in real time-like a live video of drug transport. This could one day let doctors adjust doses based on how much actually reaches the baby.

What You Can Do: Safer Choices in Pregnancy

If you’re pregnant or planning to be, here’s what matters:

- Don’t stop prescribed meds without talking to your doctor. Untreated depression, epilepsy, or high blood pressure can be more dangerous than the medication.

- Ask about placental transfer. Not all doctors know the details. But you can ask: “Does this cross the placenta? Is there data on fetal exposure?”

- Use the lowest effective dose. Especially in the first trimester. Less drug = less risk.

- Avoid OTC drugs unless approved. Herbal supplements, pain relievers, cold meds-they all cross. Just because they’re “natural” doesn’t mean they’re safe.

- Track your meds. Keep a list of everything you take, including vitamins and supplements. Bring it to every appointment.

There’s no perfect answer. But there are better ones. The goal isn’t to avoid all medication-it’s to use the right one, at the right time, in the right amount.

The Future: Targeted Therapy and Ethical Challenges

Scientists are now trying to design drugs that don’t cross the placenta at all-or ones that only cross when needed. Imagine a cancer drug that’s locked until it reaches the tumor. Or a therapy that delivers insulin directly to the fetal pancreas without flooding the rest of the body.

But this is risky. If we can control what crosses, we might also accidentally trap something vital. Or cause buildup in the placenta itself. Nanoparticles, for example, could accumulate and trigger inflammation. Early studies show this might harm placental function.

The biggest challenge isn’t science-it’s ethics. We need better data. But we can’t test on pregnant women. So we rely on animal models, lab-grown tissue, and post-birth monitoring. It’s slow. It’s imperfect. But it’s all we have.

The thalidomide disaster changed medicine. It forced regulators to demand proof of safety before a drug hits the market. Today, the FDA requires placental transfer data for new drugs. That’s progress. But it’s not enough. We still treat pregnancy like an exception-not a normal part of human biology.

The truth is, every medication a pregnant person takes is a conversation between two lives. The placenta doesn’t choose. It follows physics, chemistry, and biology. We’re the ones who need to understand the rules-and make better choices.

Can all medications cross the placenta?

No. Whether a medication crosses depends on its size, lipid solubility, protein binding, and ionization. Small, fat-soluble drugs like alcohol and nicotine cross easily. Large or charged molecules like insulin or heparin barely pass. The placenta also has active transporters that push some drugs back out, like P-glycoprotein and BCRP.

Is it safe to take antidepressants during pregnancy?

Some antidepressants, like sertraline and citalopram, cross the placenta but are considered among the safest options. About 30% of babies exposed late in pregnancy show temporary symptoms like fussiness or feeding issues, but these usually resolve within days. Untreated depression carries its own risks, including preterm birth and low birth weight. Always work with your doctor to weigh risks and benefits.

Why is the first trimester more dangerous for drug exposure?

The placenta is still developing in the first trimester. Protective transporters like P-gp and BCRP aren’t fully active, and the barrier between mother and baby is thinner. This makes it easier for drugs to reach the fetus during critical organ formation-weeks 4 to 12. That’s why exposure to thalidomide or valproic acid early in pregnancy causes severe birth defects.

Do over-the-counter drugs like ibuprofen or cold medicine cross the placenta?

Yes. Many OTC drugs cross easily. Ibuprofen can reduce amniotic fluid and affect fetal heart development if taken after 20 weeks. Decongestants like pseudoephedrine can restrict blood flow to the placenta. Even herbal supplements like echinacea or ginger can have effects. Always check with your provider before taking anything.

How do researchers study drug transfer today?

Modern methods include dually perfused human placenta models, placental membrane vesicles, and placenta-on-a-chip devices that mimic real tissue. Non-invasive imaging with radioactive tracers lets scientists watch drug movement in real time. These tools are far more accurate than animal studies, which often don’t reflect human placental biology.

Are there any medications that are completely safe in pregnancy?

There’s no such thing as “completely safe.” Even acetaminophen, often considered the safest pain reliever, has been linked to subtle developmental effects with long-term use. The goal isn’t to find zero-risk drugs-it’s to find the lowest-risk option for your specific condition. Always discuss alternatives with your healthcare provider.

Uzoamaka Nwankpa January 4, 2026

The placenta isn’t a wall, it’s a gatekeeper-and that changes everything. I never realized how much of what I took during my pregnancy was literally swimming through to my kid. I was on sertraline and didn’t think twice. Now I wonder if the sleepless nights at 3 months were just withdrawal or if the drug was still whispering in his nervous system.

It’s terrifying how little we’re told. No one warned me about ibuprofen in the first trimester. I took it for headaches like it was aspirin. Now I’m stuck with the guilt of not knowing better.

They say ‘trust your doctor,’ but most OBs don’t know the pharmacokinetics. They just say ‘it’s fine.’ I wish someone had said: ‘Here’s how it moves. Here’s what it might do.’

Chris Cantey January 4, 2026

There’s a deeper metaphysical layer here. The placenta isn’t just a biological filter-it’s a silent negotiator between two sovereign entities. The mother’s body doesn’t ‘own’ the fetus; it hosts it. And the drugs? They’re the ghosts in that contract. We assume autonomy, but biology doesn’t care about consent. It only obeys diffusion gradients and transporter proteins.

Is it ethical to treat pregnancy as a medical edge case? Or should we recognize it as a unique physiological state that demands its own pharmacopeia? We’re still using adult drug models on a system that evolved over millions of years to protect life. That’s not science. That’s arrogance dressed in lab coats.

Abhishek Mondal January 6, 2026

Metaphysical? You’re overcomplicating it. The placenta doesn’t ‘negotiate’-it follows thermodynamics. And your ‘sovereign entities’ nonsense ignores that the fetus is genetically half-foreign. The mother’s immune system tolerates it-despite the fact that it’s essentially a semi-allograft. That’s not philosophy; that’s immunology. And the fact that P-gp actively excludes toxins? That’s evolution optimizing for survival-not some cosmic balance.

Also, ‘pharmacopeia for pregnancy’? We don’t need a new drug class-we need better clinical trials. The problem isn’t the biology. It’s the lack of data. Stop romanticizing the placenta. It’s not a philosopher. It’s a protein pump.

Oluwapelumi Yakubu January 7, 2026

Man, this whole thing is wild. I read this and thought-wow, we’re basically giving our babies a secret cocktail they didn’t sign up for. And we call it ‘medicine.’

Remember when my cousin took that herbal tea for ‘nausea’ and her baby had a heart defect? No one told her ginger could mess with fetal circulation. ‘Natural’ doesn’t mean ‘safe.’ It just means ‘unregulated.’

And the fact that methadone can block BCRP and let chemo sneak in? That’s like giving a thief the master key to the vault. We’re playing Jenga with fetal development and pretending the blocks won’t fall.

Why don’t we have a placental transfer app? Like a drug safety scanner? ‘Scan your pill → see % to fetus.’ I’d use that. I’d pay for that. Someone make this.

Terri Gladden January 9, 2026

Ok but what if the FDA is lying? I mean-why do they say 45% of drugs have no data? What if it’s 80%? And what if they’re just not telling us because they’re scared of lawsuits? Like… what if they know but they’re hiding it? I saw a documentary once where they said they used to test drugs on pregnant women in the 50s and then just… stopped. Why? Because they got caught? Or because they didn’t want to admit they’d been poisoning babies for decades?

Also-why is everyone so calm about SSRIs? My sister’s kid had seizures after birth. They said ‘it’s normal.’ But it wasn’t normal. It was terrifying. And now he’s on speech therapy. Who approved this? Who said it was fine?

Jennifer Glass January 9, 2026

I appreciate how thorough this is. The detail on lipid solubility and ionization is exactly what’s missing from patient education.

I’m a nurse and I’ve had patients stop their blood pressure meds because they were scared of ‘hurting the baby.’ But uncontrolled hypertension is far riskier than lisinopril. We need better tools to translate this science into plain language.

Also-this is the first time I’ve seen someone explain why insulin is safe. Most patients think ‘injecting anything = danger.’ The fact that it’s too large to cross is such a simple, elegant answer. Why isn’t this on every prenatal handout?

And yes-placenta-on-a-chip tech? That’s the future. We need to fund it. Not just for drugs, but for environmental toxins too. Lead, phthalates, microplastics-they all cross. We’re blind to most of them.

Joseph Snow January 11, 2026

This entire article reads like a corporate PR piece disguised as science. Who funded this? Big Pharma? Because the narrative is too convenient: ‘We don’t know enough, but here’s a list of safe drugs.’

Let’s be real-no drug is ‘safe’ in pregnancy. The FDA’s ‘Category C’ classification is a joke. It means ‘we tested it on rats and they didn’t explode.’ That’s not evidence. That’s hope.

And why is no one talking about the fact that most of these ‘safe’ drugs were never tested on pregnant women? They’re just assumed safe because they’re old. That’s not science. That’s tradition. And tradition got us thalidomide.

Don’t trust the system. Question everything. And if you’re pregnant-don’t take anything unless you’re dying.

melissa cucic January 12, 2026

I understand your skepticism-but dismissing all research because of past failures is like refusing to fly because of one plane crash. The FDA’s current requirements-placental transfer data, teratology studies, post-marketing surveillance-are far more rigorous than they were in the 1960s.

Yes, animal models are imperfect. But placental perfusion studies and organ-on-a-chip models are now giving us human-relevant data. We’re not relying on rats anymore.

And while no drug is 100% risk-free, we also can’t ignore the risk of untreated maternal illness. Depression, seizures, hypertension-they kill mothers and babies too.

The goal isn’t zero risk. It’s informed, calibrated risk. That’s what this article is trying to say. Not ‘everything’s fine.’ But ‘here’s what we know-and here’s how to use it wisely.’

Akshaya Gandra _ Student - EastCaryMS January 13, 2026

so like… if i took tylenol for a headache at 6 weeks and now im 20 weeks… is my baby gonna be ok?? i mean i read the part about ibuprofen but tylenol is different right?? like i dont want to panic but also i cant stop thinking about it now??

also why dont they just make a chart? like a big poster in the doctor's office? with pictures of pills and green/yellow/red for how much crosses?? that would help so much