Multiple sclerosis isn’t just about flare-ups and fatigue. For many people, it’s a slow, quiet erosion of movement, sensation, and independence - a neurological decline that doesn’t always show up on an MRI. While relapses can be scary, the real long-term threat isn’t the inflammation you can see. It’s the hidden damage: axons dying, neurons vanishing, and the brain’s ability to compensate running out of steam.

What’s Really Happening Inside the Nervous System?

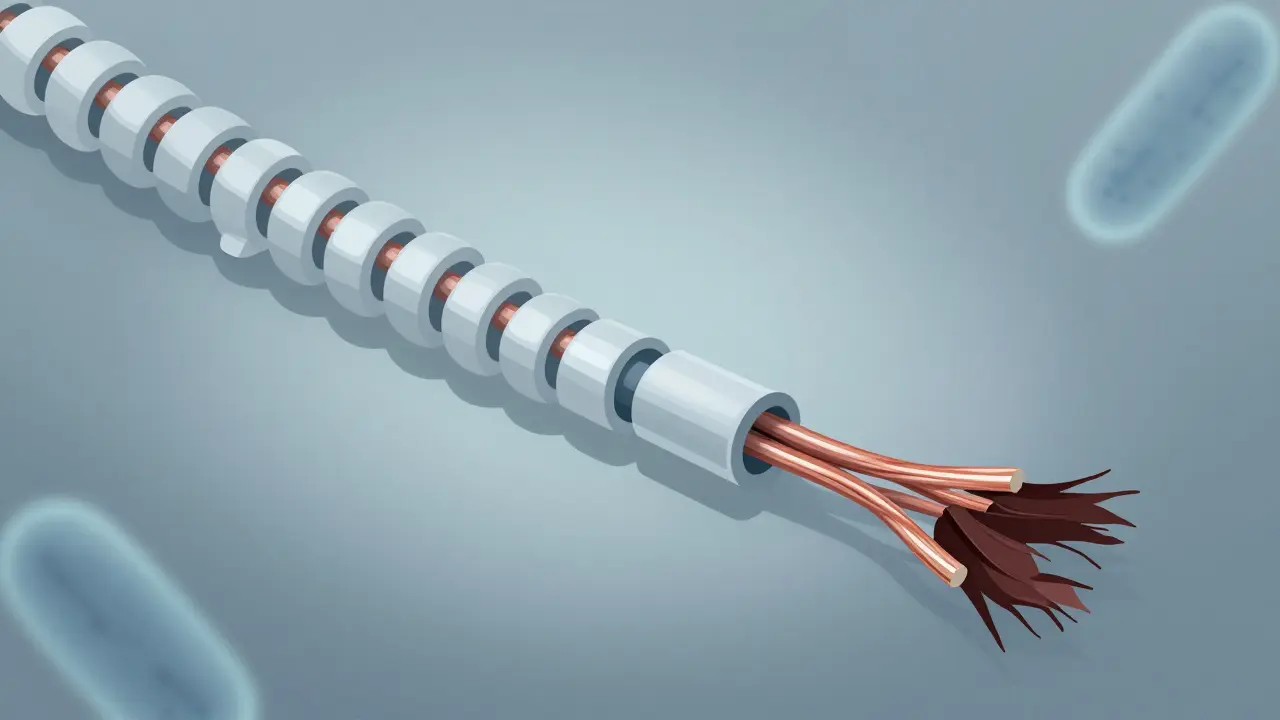

Multiple sclerosis starts with the immune system attacking the myelin sheath - the fatty insulation around nerve fibers in the brain and spinal cord. Think of myelin like the plastic coating on an electrical wire. When it’s stripped away, signals between the brain and body slow down or get blocked. That’s what causes the numbness, blurred vision, or leg weakness during a relapse.

But here’s the catch: the body can repair some of this damage. New myelin can form, and nerves can reroute signals. That’s why many people recover after a flare-up. The real problem isn’t just the loss of myelin - it’s what happens after. When axons - the actual nerve fibers - are left exposed for too long, they start to degenerate. And once an axon dies, it doesn’t come back.

Studies show that up to 50% of demyelinated axons in chronic MS lesions show signs of metabolic collapse: mitochondria are gone, microtubules are fragmented, and the internal structure of the nerve fiber breaks down. This isn’t inflammation anymore. This is neurodegeneration. And it’s irreversible.

Why Some People Progress, and Others Don’t

Eighty-five percent of people are diagnosed with relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS). For them, symptoms come and go. But over time, about 40% will shift into secondary progressive MS (SPMS). In this phase, the relapses become less frequent - but the decline continues. Why?

Early MS is driven by immune cells from the bloodstream crossing into the brain and causing damage. But as the disease ages, the fire shifts inside the central nervous system itself. Immune cells that live in the brain - especially B cells clustered near the meninges - keep burning. These aren’t the same immune cells that respond to current drugs. That’s why treatments that work wonders for RRMS often stop working in SPMS.

What’s worse? People with SPMS who develop follicle-like structures in their meninges - essentially immune cell nests - tend to get sick earlier, decline faster, and have a 2.3 times higher risk of death. These aren’t just random findings. They’re biological red flags.

The Limits of Current Treatments

There are 21 FDA-approved disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) for MS. Most of them reduce relapses by 30-50%. Some even cut new brain lesions on MRI by 80%. But here’s what they don’t do: stop the slow death of axons.

Drugs like interferons, glatiramer acetate, fingolimod, and ocrelizumab are powerful against inflammation. They help you avoid new attacks. But they don’t fix the damage already done. And when MS moves into its progressive phase - where inflammation fades but disability climbs - these drugs often offer little to no benefit.

That’s the cruel paradox of MS treatment today: we can control the flare-ups, but we can’t stop the erosion. A person might take a DMT for years, have zero new lesions, and still lose the ability to walk. Why? Because the disease has moved underground.

Neurodegeneration: The Silent Killer

Neurological decline in MS isn’t random. It’s tied to measurable brain changes. Brain atrophy - the shrinking of brain tissue - is one of the strongest predictors of future disability. Studies show that the rate of gray matter loss over four years predicts functional decline six years later. Gray matter is where nerve cell bodies live. When it shrinks, the brain loses processing power.

Even areas that look normal on MRI - called normal-appearing white matter - show signs of damage. Magnetization transfer ratio (MTR) scans reveal subtle changes in these regions: microglial activation, early axon loss, and metabolic stress. These changes happen long before symptoms appear.

And then there’s the sodium problem. Healthy nerves use sodium channels to send signals. In MS, these channels become dysfunctional or disappear. Without them, nerves can’t fire properly - even if the myelin is partially restored. This isn’t just about insulation. It’s about the wire itself failing.

What’s on the Horizon?

Researchers aren’t giving up. Over 17 active clinical trials are now targeting the neurodegenerative side of MS - not just the inflammation. These include:

- Neuroprotective agents: Drugs that protect mitochondria, the energy factories inside nerve cells. If axons can’t produce enough energy, they die.

- Sodium channel blockers: Medications that stabilize nerve signaling and prevent sodium overload, which can kill neurons.

- Remyelination therapies: Drugs like opicinumab and clemastine that try to jump-start the body’s own repair system to rebuild myelin.

- B-cell targeting in the CNS: New drugs designed to penetrate the brain and shut down the meningeal B-cell clusters that drive progression.

One promising area is the role of astrocytes - support cells in the brain. Their β2-adrenergic receptors, which help regulate inflammation and metabolism, are lost in MS. Restoring these receptors with targeted drugs could slow both damage and degeneration.

And then there’s the question of regeneration. The CNS doesn’t heal like skin or bone. Three proteins - Nogo, MAG, and OMgp - act like stop signs for nerve regrowth. Blocking these with antibodies or gene therapies could one day allow damaged axons to reconnect. It’s still experimental, but it’s no longer science fiction.

What You Can Do Now

While we wait for breakthrough drugs, there are concrete steps that can make a difference:

- Start treatment early: The sooner you begin a DMT after diagnosis, the more axons you preserve. Delaying treatment increases long-term disability risk.

- Monitor brain volume: Ask your neurologist about annual MRI scans that measure brain atrophy - not just new lesions. This tells you if your treatment is protecting your brain.

- Manage lifestyle factors: Vitamin D deficiency, smoking, and obesity are linked to faster progression. Quitting smoking alone can reduce relapse risk by 30%.

- Exercise consistently: Aerobic activity, strength training, and balance work don’t just improve function - they may actually stimulate neuroprotective factors in the brain.

- Track function, not just symptoms: The Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) misses subtle decline. The Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite (MSFC) - which tests walking, hand movement, and cognition - gives a clearer picture of real-world progression.

The Future Is in the Brain, Not Just the Blood

Multiple sclerosis is changing from a disease of immune attacks to a disease of brain failure. We’ve made huge progress controlling the inflammation. Now we need to turn our attention to the neurons.

For patients in the relapsing phase, today’s DMTs are life-changing. But for those in the progressive phase - or those worried about what’s coming next - the message is clear: we need better tools. Not just to prevent relapses, but to prevent the silent, steady loss of the brain’s ability to function.

The next decade of MS research won’t be about more pills to reduce flare-ups. It’ll be about saving the nerve fibers that carry your thoughts, your movements, your independence. And that’s a fight worth winning.

Spencer Garcia December 24, 2025

Early treatment is everything. I started on a DMT six months after diagnosis and my atrophy rate dropped to near zero. Don't wait for symptoms to get worse - the damage is already stacking up silently.

Abby Polhill December 25, 2025

The meningeal B-cell follicles are the real villains here - they’re like little inflammatory nests that just keep churning out cytokines and neurotoxins. Current DMTs don’t penetrate the CNS well enough, which is why SPMS progression feels like running on a treadmill that’s slowly accelerating.

Bret Freeman December 25, 2025

Let me tell you something - the pharmaceutical companies don’t want you to know this, but they’ve known for over a decade that neurodegeneration is the real killer. They keep selling you pills that reduce lesions because those are easy to measure and FDA-approved. Meanwhile, your neurons are turning to dust and they’re still charging you $80,000 a year. This isn’t medicine. It’s a money machine.

Austin LeBlanc December 27, 2025

You’re all missing the point. If you’re not doing at least 45 minutes of HIIT and taking 5,000 IU of vitamin D3 daily, you’re just enabling your own decline. And if you smoke? You’re a walking liability. Stop blaming the disease and start taking responsibility.

niharika hardikar December 27, 2025

It is imperative to acknowledge that the current therapeutic paradigm remains fundamentally reactive rather than proactive. The persistent failure to target intrathecal B-cell aggregates and mitochondrial dysfunction represents a critical gap in clinical neurology. Without longitudinal neuroimaging biomarkers, therapeutic efficacy remains empirically approximated.

John Pearce CP December 28, 2025

There is no excuse for delaying treatment. In my country, we don't wait for disaster to strike before we act. If you're diagnosed with MS and you're not on a DMT within 90 days, you're not just being careless - you're betraying your future self. This isn't a suggestion. It's a survival protocol.

Georgia Brach December 29, 2025

Let’s be honest - neuroprotective agents have a 98% failure rate in phase 3 trials. Remyelination therapies? Mostly snake oil wrapped in fancy MRI data. The real reason we haven’t stopped progression is because the biology is too complex, and the industry is too invested in selling inflammation blockers. Don’t get fooled by hope.

Diana Alime December 30, 2025

so like… i just found out my brain is shrinking and im supposed to exercise and take vit d? cool. guess ill just… stop eating carbs now and pray. also my neurologist said "maybe" try ocrelizumab. thanks for the info i guess??