When your lungs feel like they’re wrapped in a tight band, and every breath feels like a struggle, it’s not just being out of shape. That’s often the first sign of pleural effusion-fluid building up between the layers of tissue that surround your lungs. It doesn’t always hurt, but it always makes breathing harder. And if left unaddressed, it can signal something serious-like heart failure, pneumonia, or even cancer.

What Causes Pleural Effusion?

Pleural effusion isn’t a disease on its own. It’s a symptom. The fluid builds up because something in your body is out of balance. There are two main types: transudative and exudative.Transudative effusions happen when fluid leaks out because of pressure changes. Think of it like water seeping through a weak spot in a dam. The most common cause? Congestive heart failure. It’s responsible for about half of all transudative cases. When your heart can’t pump blood effectively, pressure builds in the veins leading to the lungs, forcing fluid into the pleural space. Liver cirrhosis and kidney disease (nephrotic syndrome) are other big players here. In these cases, your body isn’t making enough protein-or losing too much-so fluid escapes from blood vessels.

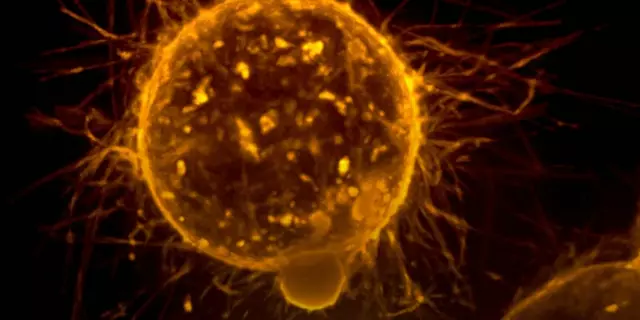

Exudative effusions are different. They’re caused by inflammation, infection, or cancer. The tiny blood vessels in the pleura become leaky, like a broken pipe. Pneumonia is the top cause, accounting for 40-50% of exudative cases. When lung tissue gets infected, the body sends immune cells and fluid to fight it-but sometimes too much accumulates. Cancer, especially lung or breast cancer that spreads to the lining of the lungs, causes 25-30% of these cases. Pulmonary embolism (a blood clot in the lung) and tuberculosis are less common but still important to rule out.

One key detail: doctors don’t guess the type. They test the fluid. Back in 1972, Dr. Richard Light created a set of rules-now called Light’s criteria-that tell you whether fluid is transudative or exudative. If the fluid protein is more than half the blood protein, or if LDH (a cell damage marker) is over two-thirds of the blood level, it’s exudative. These rules are 99.5% accurate. Missing this step means missing the real problem.

How Thoracentesis Works and When It’s Needed

If fluid is building up and you’re short of breath, doctors will often drain it. That procedure is called thoracentesis. It’s not surgery. It’s a quick needle stick-done under ultrasound guidance-usually between your ribs on the side of your chest.Ultrasound isn’t optional anymore. Ten years ago, doctors sometimes did this blind. Now, every major guideline says ultrasound is required. Why? Because without it, you risk puncturing your lung. About 1 in 5 patients had a collapsed lung back then. Today, with ultrasound, that drops to less than 5%. That’s an 80% reduction in complications.

The needle is thin-18 to 22 gauge-and goes in just deep enough to reach the fluid. For diagnosis, they take 50 to 100 milliliters. For relief, they can safely remove up to 1,500 milliliters in one session. But there’s a catch: removing too much too fast can cause something called re-expansion pulmonary edema. Your lung, squeezed for days, suddenly expands again and starts leaking fluid into itself. That’s rare-under 1%-but it’s serious.

What do they test in that fluid? Protein, LDH, cell count, pH, glucose, and cytology (looking for cancer cells). A pH below 7.2 means the fluid is acidic-often from a complicated pneumonia. Glucose under 60 mg/dL suggests infection or rheumatoid arthritis. LDH over 1,000 IU/L? That’s a red flag for cancer. And if they find cancer cells? That’s a diagnosis. Cytology finds cancer in about 60% of malignant cases. Sometimes, they need more tests-like amylase (for pancreatitis-related fluid) or hematocrit (if there’s blood, it could mean a clot or trauma).

Preventing Recurrence: It Depends on the Cause

Draining the fluid helps you breathe better. But if you don’t fix the root cause, it comes back. And fast.For heart failure patients, recurrence drops from 40% to under 15% when they’re on the right meds-diuretics to flush out fluid, ACE inhibitors or beta-blockers to improve heart function. Monitoring NT-pro-BNP levels helps doctors adjust treatment before fluid builds up again.

For pneumonia-related effusions, antibiotics are the first step. But if the fluid is thick, infected, or has low pH and glucose, it won’t clear on its own. That’s when drainage becomes critical. Without it, 30-40% of cases turn into empyema-pus in the chest. That’s a hospital stay, IV antibiotics, and sometimes surgery.

But the biggest challenge is malignant pleural effusion. Cancer patients have a 50% chance of fluid returning within 30 days after just one drainage. That’s why doctors don’t stop at thoracentesis.

Two main options exist: pleurodesis and indwelling pleural catheters. Pleurodesis means sticking the lung lining to the chest wall so fluid can’t collect. Talc is the most common agent-it’s dusted into the chest and causes inflammation that fuses the layers. Success? 70-90%. But it’s painful. Up to 80% of patients need strong painkillers afterward. And it requires a hospital stay of 3-5 days.

Indwelling pleural catheters are changing the game. A thin tube is placed in the chest and left in place. Patients drain the fluid at home, a few times a week. No hospital stay. Less pain. And better quality of life. Studies show 85-90% of patients stay free of fluid buildup after six months. In a 2021 trial, patients with these catheters spent an average of 2.1 days in the hospital-down from 7.2 with traditional pleurodesis.

What Doesn’t Work

Not every fluid collection needs to be drained. If the effusion is small, under 10mm on ultrasound, and you’re not short of breath, doctors should hold off. A 2019 JAMA study found that 30% of thoracentesis procedures were done on patients who didn’t benefit at all-no symptom relief, no new diagnosis. That’s unnecessary risk.And don’t use chemical pleurodesis for non-cancer cases. The American Thoracic Society says there’s no proof it helps for heart failure, liver disease, or kidney-related effusions. You’re just causing inflammation for no reason.

The Bigger Picture

Treating pleural effusion without treating the cause is like bailing water from a sinking boat without fixing the hole. That’s what Dr. Light said in 2018-and it’s still true today.The real progress isn’t in the needle. It’s in the thinking. We now know that fluid analysis isn’t optional. Ultrasound isn’t optional. And personalized care based on the cause isn’t optional. For cancer patients, survival has improved-from 10% alive at five years in 2010 to 25% today-because we’re treating the cancer better, not just the fluid.

Today, the goal isn’t just to remove fluid. It’s to restore breathing, reduce hospital visits, and keep patients at home. That’s what matters.

Can pleural effusion go away on its own?

Sometimes, yes-but only if it’s small and caused by something mild, like a minor viral infection. Most cases, especially those linked to heart failure, pneumonia, or cancer, won’t resolve without treatment. Waiting can lead to complications like infection, lung collapse, or permanent scarring. If you’re diagnosed with pleural effusion, follow-up testing is essential.

Is thoracentesis painful?

You’ll feel pressure when the needle goes in, and a brief sting from the local anesthetic. Most patients say it’s uncomfortable but not unbearable. After the procedure, you might have mild soreness for a day or two. Serious pain is rare. If you feel sharp chest pain or sudden shortness of breath afterward, call your doctor immediately-it could mean a collapsed lung.

How long does it take to recover after thoracentesis?

Most people feel better right away, especially if they were struggling to breathe. You can usually go home the same day if there are no complications. Avoid heavy lifting or strenuous activity for 24-48 hours. If you have an indwelling catheter, you’ll need to drain it regularly at home and keep the site clean to prevent infection.

What are the signs that pleural effusion is coming back?

The same symptoms you had before: shortness of breath, especially when lying down or exerting yourself, a dry cough, or feeling tightness in your chest. If you’ve had a malignant effusion before and notice these returning, don’t wait. Contact your oncologist or pulmonologist. Early drainage and management can prevent hospitalization and improve comfort.

Can pleural effusion be prevented?

You can’t always prevent it, but you can reduce your risk by managing the conditions that cause it. Control heart failure with medication and diet. Quit smoking to lower lung cancer and pneumonia risk. Get vaccinated for flu and pneumonia if you’re over 65 or have chronic illness. If you’ve had one effusion, regular check-ups and monitoring (like chest X-rays or ultrasounds) can catch recurrence early.

Are there alternatives to thoracentesis?

For small, asymptomatic effusions, no-monitoring is enough. For larger ones, thoracentesis is the first step. But if fluid keeps coming back, indwelling pleural catheters are now preferred over repeated thoracentesis or chemical pleurodesis, especially for cancer patients. They offer better control, fewer hospital visits, and higher quality of life. Surgery (pleurectomy) is rare and only considered if other methods fail.

What Comes Next?

If you’ve been diagnosed with pleural effusion, your next steps depend on the cause. Ask your doctor: Is this transudative or exudative? What’s the fluid analysis showing? What’s the plan if it comes back?Don’t accept vague answers. Demand the test results. Push for ultrasound-guided drainage if needed. And if cancer is suspected, ask about cytology and whether an indwelling catheter might be right for you.

Pleural effusion isn’t just a fluid problem. It’s a signal. And the best way to handle it is to listen to what your body-and your tests-are telling you.

Konika Choudhury January 11, 2026

Finally someone talks sense about pleural effusion instead of just pushing meds

India’s got tons of these cases from TB and heart failure and no one checks the fluid

Light’s criteria isn’t optional it’s gospel

Stop draining for fun and start testing

Darryl Perry January 13, 2026

The data is clear. Thoracentesis without ultrasound is malpractice. The 80% reduction in pneumothorax is not a suggestion-it is a standard. Failure to comply constitutes negligence.

Windie Wilson January 15, 2026

Oh wow. A medical article that doesn’t sound like it was written by a robot on caffeine. Who knew? Maybe if doctors actually read this instead of scrolling TikTok, we wouldn’t have 30% of thoracenteses done on people who don’t need them.

Daniel Pate January 16, 2026

It’s fascinating how we treat symptoms as problems rather than signals. Pleural effusion isn’t the disease-it’s the messenger. The real question isn’t how to remove fluid, but why the body is producing it in the first place. Medicine still struggles with systems thinking. We fix pipes while ignoring the broken water pressure valve.

Jose Mecanico January 17, 2026

I’ve seen this play out in the ER-patients come in gasping, we drain 1.2L, they breathe easy, and leave without follow-up. Then they’re back in two weeks. We need better systems to connect diagnosis to long-term care. This post nails it.

Cecelia Alta January 17, 2026

Okay but let’s be real-how many of these ‘indwelling catheters’ are just fancy versions of the old chest tubes that got repackaged with a fancy name and a $2000 price tag? And don’t get me started on talc pleurodesis. I’ve seen patients scream for three days after that stuff. It’s like sticking a blowtorch in your ribcage and calling it ‘medicine.’

Meanwhile, the real solution? Stop letting oncologists treat effusions like they’re some kind of plumbing emergency. It’s cancer. You’re not fixing a leak-you’re fighting a war. And if your only weapon is a needle, you’re gonna lose.

steve ker January 19, 2026

Light’s criteria? Overrated. Most doctors don’t even know what LDH stands for. They just do scans and guess. The real problem is healthcare systems that value speed over accuracy. No one has time to think anymore.

George Bridges January 19, 2026

I appreciate how this breaks down the science without drowning in jargon. My aunt had malignant effusion last year-she got the indwelling catheter. She’s been home for months, draining it herself twice a week. No hospital stays. No pain. Just dignity. This isn’t just medicine-it’s humanity.

Faith Wright January 20, 2026

So let me get this straight-you’re telling me the best thing for cancer patients isn’t more chemo or surgery, but a tiny tube they can manage at home? And it’s cheaper and less painful? Wow. I guess medicine finally realized that patients aren’t machines that need fixing, but people who need to live.

Rebekah Cobbson January 22, 2026

If you’ve had one effusion, you’re at risk. Don’t wait until you’re gasping again. Ask for follow-up ultrasounds every 3–6 months. Keep your NT-proBNP tracked. Stay on your diuretics. It’s not scary-it’s just smart. You’ve got this. And if your doctor won’t listen? Find one who will.