Primary sclerosing cholangitis is not just another liver problem. It’s a slow, silent destroyer of the bile ducts - the tubes that carry digestive fluid from the liver to the intestines. Unlike common liver conditions like fatty liver or hepatitis, PSC doesn’t come with obvious warning signs. Many people live for years without knowing they have it. By the time symptoms appear, the damage is often already advanced. There’s no cure. No pill can stop it. But understanding what it is, how it progresses, and how to manage it can make all the difference in staying alive and feeling better.

What Happens Inside Your Body With PSC?

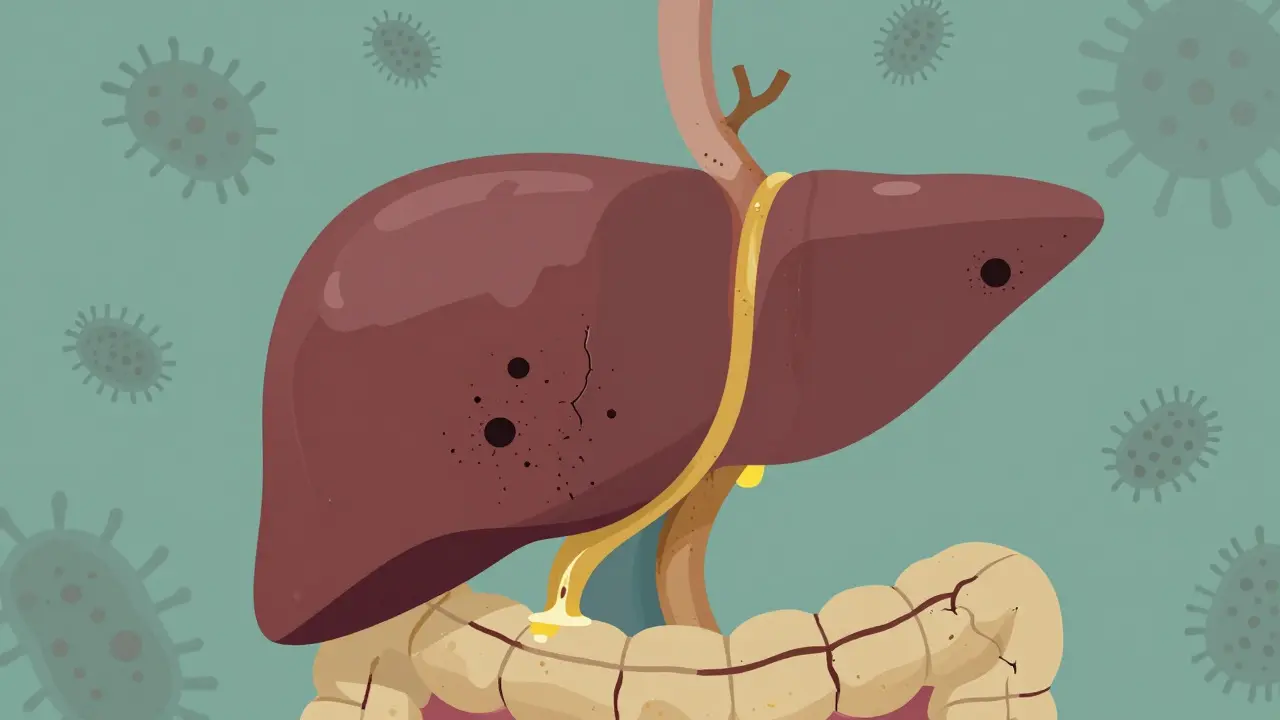

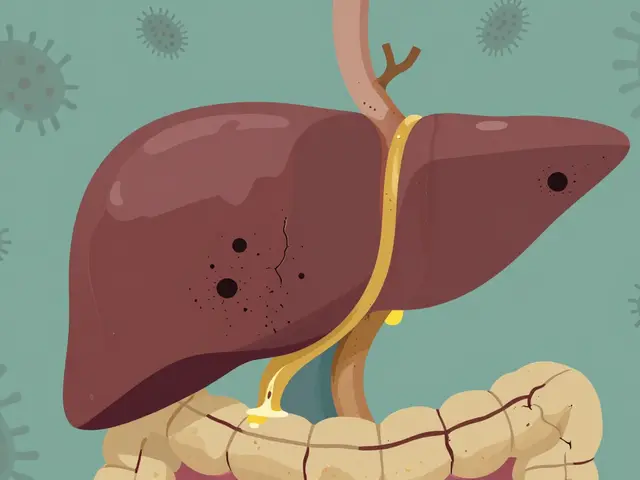

In primary sclerosing cholangitis, the body’s immune system turns against the bile ducts. It doesn’t attack liver cells like in hepatitis. Instead, it targets the tubes that carry bile - the fluid your liver makes to help digest fat. Over time, these ducts become inflamed, scarred, and narrowed. Think of it like rust building up inside a pipe until water barely flows through. In PSC, bile can’t move properly. It backs up in the liver, poisoning liver cells, causing more scarring, and eventually leading to cirrhosis - a hard, shrunken liver that can’t function.

The disease affects both the ducts inside the liver (intrahepatic) and those outside (extrahepatic). On imaging tests like MRCP, the ducts look like a tree with broken branches - uneven, blocked, and knotted. Normal bile ducts are 3 to 8 millimeters wide. In PSC, they can shrink to under 1.5 millimeters. This isn’t just a structural change; it’s a functional disaster. Without proper bile flow, your body can’t absorb fats or fat-soluble vitamins like A, D, E, and K. That’s why many patients develop bone thinning, night blindness, or easy bruising long before they feel jaundiced.

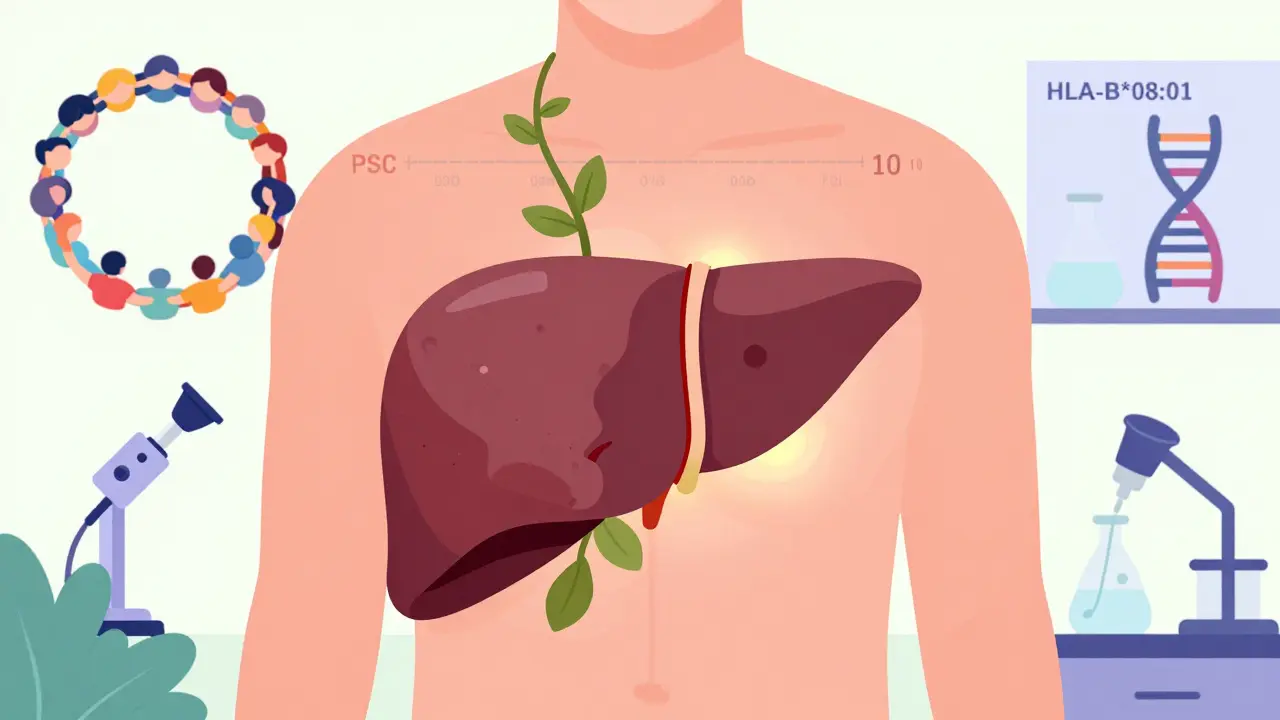

Who Gets PSC - And Why?

PSC is rare. About 1 in 100,000 people have it. But in places like Sweden, the rate is higher - nearly 6 in 100,000. It’s most often diagnosed between ages 30 and 50, with the average age being 40. Men are twice as likely to get it as women. And while it can happen to anyone, over 90% of diagnosed cases are in people of European descent.

But genetics alone don’t cause PSC. You need a trigger. And that trigger usually comes from your gut. Nearly 70% of people with PSC also have inflammatory bowel disease - most often ulcerative colitis. The connection is so strong, doctors check for PSC in every new ulcerative colitis patient. The theory? Bacteria or immune cells from the inflamed colon travel through the bloodstream to the liver and start attacking the bile ducts. Studies show specific gut bacteria and their waste products may be the actual culprits. One 2019 study found the strongest genetic link to PSC is a version of the HLA-B*08:01 gene - a marker that makes your immune system more likely to misfire.

Unlike primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), another bile duct disease, PSC doesn’t show up on standard blood tests with clear antibodies. Only 20 to 50% of PSC patients test positive for p-ANCA - a weak, unreliable marker. That’s why diagnosis often takes years. Many patients wait 2 to 5 years after symptoms start before getting a correct diagnosis.

The Symptoms Nobody Talks About

Early PSC often has no symptoms at all. That’s why it’s called a silent disease. When symptoms do appear, they’re vague - fatigue, itching, feeling bloated. But the itching? That’s the one people remember. It’s not just skin-deep. Patients describe it as if the itch is coming from inside their bones, worse at night, and impossible to scratch away. One Reddit user wrote: ‘It feels like my nerves are on fire.’

Other common symptoms include:

- Yellowing of the skin and eyes (jaundice)

- Pain in the upper right abdomen

- Unexplained weight loss

- Fever and chills (signs of infection in the bile ducts)

Fatigue is the most disabling symptom. It’s not just being tired. It’s the kind of exhaustion that makes it hard to get out of bed, go to work, or play with your kids. In surveys, 92% of PSC patients report severe fatigue. And no, coffee doesn’t fix it. This fatigue comes from toxins building up in the blood because the liver can’t filter them out.

How Is PSC Diagnosed?

There’s no single blood test for PSC. Doctors use a mix of clues:

- Blood tests: High levels of ALP (alkaline phosphatase) and GGT are red flags. ALT and AST may be normal or only slightly raised - which is confusing if you’re used to hepatitis patterns.

- Imaging: MRCP (magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography) is the gold standard. It creates detailed pictures of the bile ducts without needles or radiation. It shows the characteristic ‘beaded’ or ‘pruned tree’ appearance of narrowed ducts.

- Biopsy: Sometimes a liver biopsy is done to check for scarring stages. But it’s not always needed if MRCP is clear.

- Colonoscopy: Since 60-80% of PSC patients have ulcerative colitis, doctors check the colon even if there are no digestive symptoms.

Many patients are diagnosed accidentally - during a routine blood test or when being checked for another issue. That’s why regular liver enzyme checks are critical if you have IBD.

There’s No Cure - But There Are Ways to Manage It

The hard truth: no medication has been proven to stop or reverse PSC. Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), once widely prescribed, is now discouraged. Studies show it doesn’t improve survival and may even raise the risk of complications at high doses. The European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) both say: don’t use it routinely.

So what do you do?

- Manage itching: First-line treatment is rifampicin (150-300 mg daily). It works in 50-60% of patients. If that fails, naltrexone (50 mg daily) or colesevelam (a bile acid binder) can help. Some patients need to try 3 or 4 drugs before finding relief.

- Replace vitamins: Get quarterly blood tests for vitamins A, D, E, and K. Take supplements as needed. Low vitamin D means higher fracture risk - a major concern in PSC.

- Watch for cancer: PSC raises your risk of cholangiocarcinoma (bile duct cancer) by 1.5% every year. That’s 15% over 10 years. Annual MRCP and CA19-9 blood tests are recommended. Colon cancer risk is also high - get a colonoscopy every 1-2 years if you have ulcerative colitis.

- Prevent infections: Blocked bile ducts can get infected (cholangitis). Signs: fever over 38.5°C, right-side pain, jaundice. This is an emergency. You’ll need antibiotics and often a procedure to open the blocked duct.

When Transplantation Is the Only Option

For many, liver transplant is the only long-term solution. About 10 to 15 years after diagnosis, most patients reach end-stage liver disease. The good news? Transplant success rates are excellent. Over 80% of PSC patients survive at least 5 years after transplant, according to Cleveland Clinic data. Most return to normal life - working, traveling, even having children.

But transplant isn’t a cure-all. PSC can come back in the new liver - in about 15-20% of cases. It usually takes 10 or more years to reappear. That’s why transplant centers monitor patients closely for years after surgery.

Transplant eligibility depends on liver function, complications, and overall health. It’s not about how sick you feel - it’s about how much your liver has failed. Doctors use models like MELD (Model for End-Stage Liver Disease) to decide who gets priority on the waiting list.

What’s Coming Next? Hope on the Horizon

While there’s no cure today, research is moving fast. In 2023, the FDA paused approval of obeticholic acid (OCA) due to safety concerns, but the data showed a 32% drop in liver enzymes - a sign it might slow disease. Cilofexor, a new drug targeting the FXR receptor, reduced ALP levels by 41% in early trials. Fibrates, usually used for cholesterol, are also showing promise in reducing bile acid buildup.

Researchers now believe PSC is not one disease, but several. Some patients have only small duct involvement (small-duct PSC), which progresses slower and has lower cancer risk. Others have aggressive, large-duct disease. Future treatments will likely be personalized based on these subtypes.

One of the biggest breakthroughs is the PSC Partners Seeking a Cure registry - now tracking over 3,100 patients across 12 countries. Real-world data from this group is helping scientists design better trials and find patterns no single hospital could see.

Living With PSC - What You Need to Know

Living with PSC means accepting uncertainty. You won’t know how fast it will progress. But you can control your care:

- See a specialist - not a general hepatologist. Centers that treat 50+ PSC patients a year have better outcomes.

- Keep all appointments. Blood tests, MRCPs, and colonoscopies aren’t optional - they’re life-saving.

- Join a support group. The emotional toll is real. Patients who connect with others report better mental health and adherence to treatment.

- Don’t drink alcohol. It speeds up liver damage.

- Eat a balanced diet. No special ‘PSC diet,’ but avoid processed foods and excess sugar. Fat malabsorption means you need healthy fats - like olive oil and fish - in moderation.

Most patients who stay engaged with their care live full lives for decades. The key isn’t finding a miracle drug - it’s staying informed, staying monitored, and staying connected.

Is primary sclerosing cholangitis the same as primary biliary cholangitis?

No. While both affect bile ducts, they’re different diseases. Primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) mainly damages small bile ducts inside the liver and is strongly linked to anti-mitochondrial antibodies (found in 95% of cases). PSC affects both large and small ducts inside and outside the liver and rarely shows those antibodies. PBC is more common in women, while PSC affects men twice as often. They also respond differently to treatments.

Can you die from primary sclerosing cholangitis?

Yes, if it’s not managed. PSC slowly destroys the liver and can lead to liver failure, infections, or bile duct cancer. Without a transplant, 10-year survival is around 50-77%, depending on symptoms at diagnosis. But with regular care and timely transplant, most people live for decades. The biggest threat is cholangiocarcinoma - which reduces 5-year survival to just 10-30% if not caught early.

Why does PSC cause itching?

Bile acids build up in the blood when ducts are blocked. These acids stimulate nerve endings in the skin and even deeper tissues, causing intense itching - often worse at night. It’s not just a skin reaction; it’s a systemic response to toxins your liver can’t clear. Medications like rifampicin and naltrexone help by blocking the signals that cause the itch.

Is PSC hereditary?

It’s not directly inherited like cystic fibrosis, but genetics play a big role. If you have a close relative with PSC, your risk is higher. The strongest genetic link is the HLA-B*08:01 gene variant, which increases risk by more than double. But having the gene doesn’t mean you’ll get PSC - you also need environmental triggers, like gut bacteria or immune system changes.

Can you live a normal life with PSC?

Yes - if you stay proactive. Many people work, travel, raise families, and enjoy life for 20+ years after diagnosis. The key is seeing a specialist regularly, managing symptoms like itching and fatigue, monitoring for cancer, and taking vitamins. Avoid alcohol, eat well, and connect with other patients. While it’s a lifelong challenge, it doesn’t have to define your life.

What’s Next? Keep Moving Forward

If you’ve just been diagnosed, it’s okay to feel overwhelmed. But you’re not alone. Thousands of people are living with PSC - and many are thriving. The next five years will bring new drugs. The next ten may bring personalized treatments. Right now, your job is to stay informed, stay connected, and stay in care. That’s how you beat the odds.

Andrew Short January 17, 2026

Let me get this straight - you’re telling me people just sit around waiting for their liver to turn to concrete while some doctor shrugs and says ‘no cure’? This is why American healthcare is a joke. You don’t get diagnosed until you’re practically dead, then they hand you a pamphlet and tell you to ‘stay informed.’ Bullshit. If this were a billionaire’s kid, there’d be a clinical trial in six months. But for the rest of us? Just pray you don’t get cancer before your transplant slot opens up.

Chuck Dickson January 17, 2026

Hey - I know this sounds heavy, but I want to say this: you’re not alone. I’ve been living with PSC for 8 years now. The itching? Yeah, it’s brutal. The fatigue? Like carrying a backpack full of bricks every day. But I’m working, hiking, even teaching my niece how to fish. It’s not about waiting for a cure - it’s about building a life that still matters. Find your people. Join the PSC Partners group. Talk to someone who gets it. You’ve got this.

Robert Cassidy January 18, 2026

Look, let’s cut through the medical fluff. This isn’t just a disease - it’s a systemic failure. The body’s immune system, trained by decades of processed food, glyphosate, and corporate-controlled medicine, turns on itself. They don’t want you cured - they want you on lifelong meds, coming back every quarter for another blood draw. The real cure? Clean air. Real food. No pharmaceuticals. But you won’t hear that from the AMA or the NIH. They profit off your suffering. Wake up.

Dayanara Villafuerte January 19, 2026

Okay but the itching?? 😵💫 I had a friend with PSC and she said it felt like her bones were being licked by a thousand fire ants at 3am. Like… how is that even a thing?? And nobody talks about how exhausting it is to just *exist* when your body’s sabotaging you. Also - rifampicin? That’s the same drug they give TB patients. So we’re basically treating PSC with TB meds?? Wild. 🤯

Andrew Qu January 19, 2026

One thing that helped me: tracking my vitamin levels religiously. D3, K2, E - I got mine checked every 3 months. When my D3 dropped below 30, my knees started aching like I was 80. Started supplementing, and within 6 weeks, I could walk without groaning. It’s not glamorous, but it’s real. Also - avoid alcohol like it’s poison. Even one drink can spike your enzymes. Your liver doesn’t forgive.

kenneth pillet January 21, 2026

i got psc 5 years ago. no symptoms at first. just high alp on a routine test. now i take 3 pills a day and get mrcps every year. its not fun but i dont drink and i eat veggies. still working. life goes on

Kristin Dailey January 22, 2026

No cure? Then why are we even talking about this? Just get a transplant or die. Simple.

rachel bellet January 23, 2026

It’s fascinating how the HLA-B*08:01 allele confers a 2.3-fold increased odds ratio for PSC development, particularly in the context of concomitant ulcerative colitis - a phenotype characterized by mucosal barrier dysfunction and aberrant bacterial translocation. The cytokine milieu, particularly IL-12/IL-23 axis dysregulation, likely drives the biliary epithelial apoptosis and periductal fibrosis via Th17 polarization. Current therapeutic paradigms remain palliative due to insufficient targeting of the enterohepatic circulation axis. Future precision medicine approaches must stratify by ductal phenotype - large-duct versus small-duct - and integrate metagenomic profiling of the gut-liver axis.

Pat Dean January 25, 2026

Ugh. Another one of these ‘oh it’s so sad but we’re all just victims’ posts. Newsflash - you chose to eat gluten, dairy, sugar, and processed crap. Your gut is a sewer. Your liver is paying the price. This isn’t bad luck. It’s consequences. Stop whining and clean up your act. Maybe then you wouldn’t need a transplant.

Robert Davis January 26, 2026

Did you know that in 2021, a study showed that patients with PSC who followed a ketogenic diet had a 27% reduction in ALP levels over 12 months? No? Because the pharmaceutical industry doesn’t want you to know that. You can’t patent a diet. So they push UDCA - which doesn’t work - and keep you hooked on expensive labs and scans. The truth? Your liver can heal… if you stop feeding it poison. But nobody wants to hear that.

Eric Gebeke January 27, 2026

I’ve been reading this since 2019. I’ve watched three friends die from cholangiocarcinoma. One was 34. Another had a baby two weeks before her transplant. I’m still here. But I don’t celebrate. I don’t post happy pics. I just… keep breathing. And I hate that I’m still here while they’re not. This isn’t hope. This is survival. And it’s ugly.

Jake Moore January 28, 2026

For anyone just diagnosed: don’t panic. Don’t google for 72 hours straight. Find a PSC specialist - not just any liver doctor. Go to Mayo, Cleveland Clinic, or Johns Hopkins. They see this every week. Get your vitamins checked. Get that colonoscopy. Join the PSC Partners registry - it’s free and helps science. And if you’re itching like crazy? Try naltrexone. It’s not perfect, but it’s better than crying in the shower every night. You’re going to be okay. Not perfect. But okay.