When your kidneys aren’t working well, what you eat becomes just as important as any medication. A renal diet isn’t about losing weight or eating ‘clean’-it’s about protecting your kidneys from further damage by controlling three key minerals: sodium, potassium, and phosphorus. For people with chronic kidney disease (CKD), getting these numbers right can mean the difference between delaying dialysis and facing serious heart problems or even sudden cardiac arrest.

Why Sodium Matters in Kidney Disease

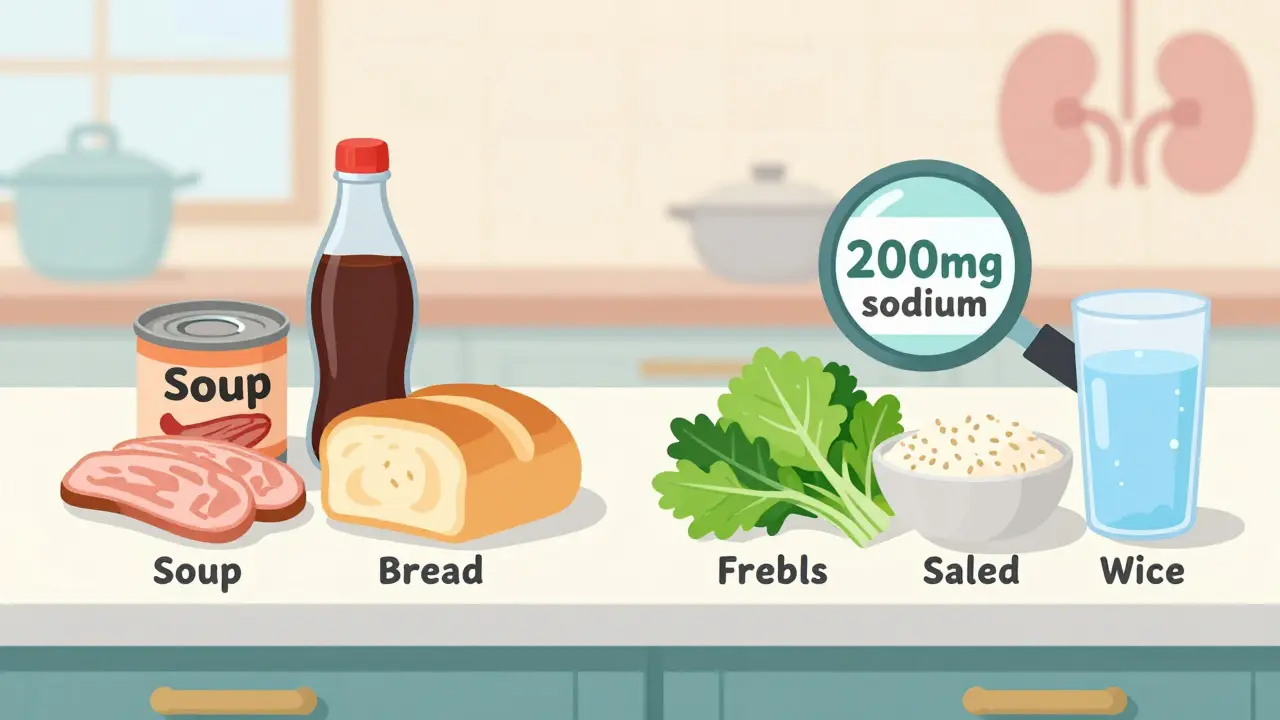

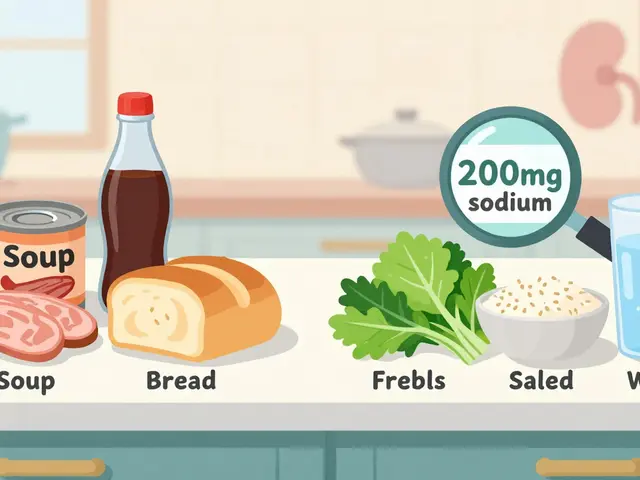

Your kidneys help balance fluid and salt in your body. When they’re damaged, they can’t remove extra sodium efficiently. That leads to fluid buildup-swollen ankles, high blood pressure, and strain on your heart. The Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines recommend limiting sodium to 2,000-2,300 mg per day for non-dialysis CKD patients. That’s about one teaspoon of salt. But here’s the catch: you’re not getting that sodium from the salt shaker. Around 75% of sodium in the average American diet comes from packaged, processed, and restaurant foods. A single can of soup can have 800-1,200 mg. One slice of deli meat? Up to 600 mg. Even bread can pack 200 mg per slice. The fix? Read labels. Look for “no salt added,” “low sodium,” or “unsalted.” Swap canned vegetables for fresh or frozen (without sauce). Choose plain rice, pasta, and oats instead of instant versions. Use herbs like basil, oregano, or garlic powder instead of salt. Studies show cutting sodium by just 1,000 mg a day can lower systolic blood pressure by 5-6 mmHg in CKD patients.Managing Potassium: The Silent Threat

Potassium helps your heart beat regularly. But when your kidneys fail, potassium builds up in your blood. Levels above 5.5 mEq/L can trigger dangerous heart rhythms-or stop your heart. That’s why many nephrologists call high potassium the “silent killer” in kidney disease. The National Kidney Foundation suggests keeping daily potassium under 2,000-3,000 mg, depending on your blood levels. But not all foods are created equal. Bananas? One has 422 mg. Oranges? 237 mg. Potatoes? A medium one has nearly 900 mg. These are common “healthy” foods-but they’re risky for CKD. Instead, choose low-potassium options: apples (150 mg each), berries (65 mg per ½ cup), cabbage (12 mg per ½ cup cooked), green beans, and cucumbers. Leaching vegetables can cut potassium by half: slice them thin, soak in warm water for 2-4 hours, then boil in plenty of water and drain. Also, remember this: potassium from animal foods (meat, dairy) is absorbed more easily than from plants. So even if you eat a plant-based diet, you still need to track portions. A 3-ounce serving of salmon has about 400 mg-fine once or twice a week, but not daily.Phosphorus: The Hidden Mineral You Can’t See

Phosphorus is everywhere-in dairy, meat, nuts, and especially in processed foods. But here’s what most people don’t know: the phosphorus added to foods (like colas, processed cheeses, and frozen meals) is absorbed almost completely-up to 90-100%. Natural phosphorus in whole foods? Only 50-70% gets absorbed. The Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI) recommends keeping daily phosphorus under 800-1,000 mg for non-dialysis CKD patients. One 12-ounce cola has 450 mg. One slice of processed cheese? 250 mg. A glass of milk? 125 mg. That’s why dietitians tell patients to avoid colas and processed cheeses entirely. Good choices? White bread (60 mg per slice) instead of whole grain (150 mg). Egg whites instead of whole eggs. Rice milk or almond milk (unsweetened) instead of dairy milk. Even small swaps add up. There’s debate in the medical community. Some European guidelines say 1,200 mg/day is fine. But U.S. experts still recommend staying under 1,000 mg because higher levels are linked to bone loss, itchy skin, and hardening of blood vessels.

Protein: The Balancing Act

You might think you need to cut protein to protect your kidneys. But too little can cause muscle loss, weakness, and infection risk-especially in older adults. Research from the Journal of Renal Nutrition found that restricting protein below 0.6 grams per kilogram of body weight increased malnutrition risk by 34%. The updated KDOQI guidelines now recommend 0.55-0.8 grams per kilogram of body weight per day. That’s about 40-60 grams for most adults. Focus on high-quality protein: eggs, lean chicken, fish, and tofu. A 3-ounce portion of cod or halibut has less sodium and moderate potassium-perfect for two to three meals a week. Avoid processed meats (bacon, sausage, deli meats). They’re high in sodium, phosphorus, and preservatives. Stick to fresh or frozen, unseasoned cuts.Real-Life Food Swaps That Work

Changing your diet doesn’t mean giving up flavor or satisfaction. It means swapping smartly:- Instead of potato chips: try air-popped popcorn (unsalted)

- Instead of orange juice: choose apple or cranberry juice (check labels for no added potassium)

- Instead of whole wheat bread: go for white bread or low-phosphorus bread

- Instead of dairy milk: use rice milk or unsweetened almond milk

- Instead of canned beans: rinse and drain them well, or use soaked and boiled dried beans

- Instead of salted butter: use olive oil with herbs

Fluids, Supplements, and Daily Habits

If your urine output is low (less than 1 liter per day), you’ll likely need to limit fluids to 32 ounces daily. That includes water, coffee, tea, soup, ice cream, and even gelatin. Sucking on ice chips or lemon wedges helps with thirst without adding volume. Phosphate binders (medications like sevelamer or calcium acetate) are often prescribed to block phosphorus absorption. But they only work if taken with meals. Skipping them defeats the purpose. Avoid herbal supplements. Many-like licorice root, stinging nettle, or dandelion-can raise potassium or harm kidneys further. Always check with your nephrologist before taking anything.

Who Needs This Diet-and When

About 37 million Americans have CKD. Ninety percent don’t know it. If you’ve been diagnosed with stage 3 or higher, this diet matters. It’s not optional. Research shows proper dietary management can delay dialysis by 6-12 months. Medicare now covers 3-6 sessions per year with a renal dietitian for stage 4 CKD patients. That’s because every dollar spent on nutrition saves $12,000 a year in avoided dialysis costs. If you have diabetes-which causes 44% of new CKD cases-you’re facing a double challenge. Heart-healthy foods for diabetics (like bananas, sweet potatoes, and nuts) are often high in potassium and phosphorus. That’s why working with a dietitian who understands both conditions is critical.What’s New in Renal Nutrition

The field is changing fast. In 2023, the FDA approved the first medical food for CKD, called Keto-1, which provides essential amino acids without phosphorus or potassium. Researchers are testing prebiotic fibers like inulin, which may reduce phosphorus absorption by 15-20%. Apps like Kidney Kitchen (downloaded over 250,000 times) let you scan barcodes and track nutrients in real time. The NIH launched the PRIORITY study in early 2024 to see if genetic testing can predict how your body handles potassium and phosphorus. That could lead to truly personalized diets-not one-size-fits-all rules. Meanwhile, experts like Dr. Sankar Navaneethan argue that extreme restriction isn’t always better. A moderate approach-focusing on food quality over strict limits-may give better long-term results without risking malnutrition.Where to Start

You don’t have to overhaul your diet overnight. Pick one thing to change this week:- Swap one high-potassium fruit for a low-potassium one

- Read the sodium label on your favorite packaged food

- Replace one soda with water or herbal tea

- Ask your doctor for a referral to a renal dietitian

Can I eat fruits and vegetables on a renal diet?

Yes-but you need to choose wisely. Low-potassium options like apples, berries, cabbage, cucumbers, and green beans are safe in normal portions. High-potassium fruits like bananas, oranges, kiwi, and dried fruit should be limited or avoided. Leaching vegetables (soaking and boiling) can reduce potassium by up to 50%. Portion control is key-even low-potassium foods can add up.

Is salt the only source of sodium in my diet?

No. Most sodium comes from processed and packaged foods-canned soups, deli meats, frozen meals, bread, and condiments. One serving of canned soup can have more sodium than a teaspoon of salt. Always check nutrition labels for “sodium” content. Look for “no salt added,” “low sodium,” or “unsalted” versions. Cooking at home with fresh ingredients gives you the most control.

Why are phosphorus additives worse than natural phosphorus?

Your body absorbs almost all the phosphorus added to processed foods-up to 90-100%. Natural phosphorus in meat, dairy, or beans is only 50-70% absorbed. Additives like sodium phosphate and phosphoric acid (found in colas, processed cheeses, and baked goods) are designed to be fully absorbed. That’s why a single cola can give you as much phosphorus as a glass of milk, even though milk has natural phosphorus. Avoiding additives is the most effective way to control phosphorus levels.

Do I need to take supplements on a renal diet?

Generally, no-and many can be dangerous. Vitamins like potassium, phosphorus, and vitamin D can build up to toxic levels if your kidneys aren’t filtering them. Some herbal supplements, like licorice or dandelion, can harm kidney function. Always talk to your nephrologist or dietitian before taking any supplement. If you’re deficient, they may prescribe a special renal vitamin that’s safe for kidney patients.

Can I still eat out at restaurants?

Yes, but it takes planning. Ask for meals prepared without added salt. Request sauces and dressings on the side. Choose grilled chicken, fish, or steak with steamed vegetables. Avoid soups, fried foods, and anything labeled “seasoned,” “marinated,” or “crispy.” Many restaurants now offer nutrition info online-check before you go. Apps like Kidney Kitchen can help you estimate sodium, potassium, and phosphorus in common dishes.

How long does it take to adjust to a renal diet?

Most people need 3 to 6 months to get used to the taste and routine. The first few weeks are the hardest-food can feel bland without salt. But over time, your taste buds adjust. Many patients say they start enjoying the natural flavors of food more. Working with a renal dietitian helps speed up the process. Keep track of how you feel: better energy, less swelling, and stable blood pressure are signs you’re on the right track.

What if I’m on dialysis? Do I still need to follow this diet?

Yes-but the rules change. Dialysis removes some sodium, potassium, and phosphorus, but not as well as healthy kidneys. You may need even stricter limits on fluids and potassium. Phosphorus control becomes even more critical because dialysis can’t fully keep up. Your dietitian will adjust your plan based on your lab results and dialysis schedule. Never assume dialysis lets you eat freely-it doesn’t.

henry mateo December 30, 2025

i just found out my bro has stage 3 ckd and i was like oh crap i’ve been feeding him canned soup and deli meat for months 😅 thanks for this guide. gonna start reading labels now. no more ‘just one can’ excuses.

Kunal Karakoti December 31, 2025

the irony is that we’ve been taught for decades that ‘natural is better’-but nature, in this case, is the enemy. potassium in bananas, phosphorus in dairy... the very things promoted as healthy are the ones we must avoid. it’s a cruel paradox of modern medicine.

Kelly Gerrard December 31, 2025

if you’re not tracking phosphorus additives you’re not serious about your health period. stop making excuses and read the ingredient list like your life depends on it because it does

Nadia Spira January 2, 2026

this is the same tired advice recycled since 2012. nobody talks about the elephant in the room: industrial food systems are designed to make you sick. the real solution isn’t ‘swap white bread for whole grain’-it’s dismantling the food industry that profits from your kidney failure. but sure, here’s a list of approved apples.

Shae Chapman January 3, 2026

omg this is so helpful!! 🙌 i just started dialysis last month and i was terrified i’d never eat anything tasty again... but the lemon-herb grilled chicken trick? life changer. also, air-popped popcorn is my new best friend 🍿❤️

Sandeep Mishra January 3, 2026

i’ve been on this diet for 4 years now. the first 6 months felt like eating cardboard. now i crave the flavor of fresh basil and garlic powder. it’s not about restriction-it’s about rediscovering real taste. and yes, i still have a glass of almond milk every morning. no regrets.

Joseph Corry January 5, 2026

let’s be honest-this diet only works if you’re rich enough to buy organic produce, specialty low-sodium products, and have the time to leach vegetables for 4 hours. most people with CKD are working two jobs and eating whatever’s cheapest. this guide is a luxury pamphlet for the privileged.

Cheyenne Sims January 6, 2026

the FDA approved a medical food called Keto-1? That’s not a breakthrough-it’s a corporate giveaway to Big Pharma. And you call this ‘nutrition’? This isn’t food. This is chemical engineering disguised as dietary advice. Shame on the medical establishment for normalizing this.

Glendon Cone January 6, 2026

i’m a nurse who works in nephrology and i can tell you-people who stick to even 70% of this diet live longer, feel better, and avoid ER trips. it’s not perfect, but it’s the best tool we’ve got. small swaps = big wins. you got this 💪

Henry Ward January 8, 2026

you people are delusional if you think swapping bread types will save you. your kidneys are failing because you lived poorly for 40 years. no amount of lemon juice or leached potatoes will undo that. stop pretending this is about food-it’s about accountability.

Aayush Khandelwal January 9, 2026

bro, the real hack? Skip the processed crap, cook with turmeric and cumin, and drink neem tea. your body’s got a self-cleaning mode-just gotta stop poisoning it with sodium bombs and phosphorus-laced soda. also, walk 30 mins a day. kidneys love movement. 🌿