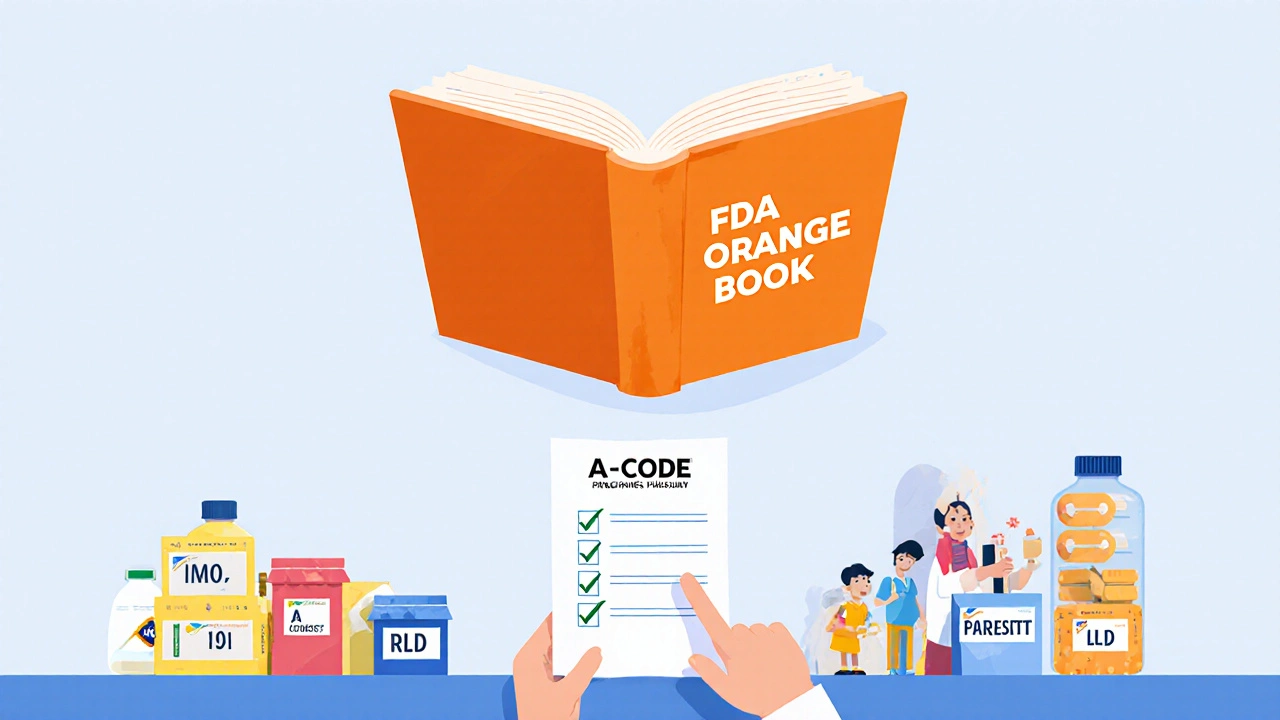

The FDA Orange Book is the official guide that tells you which generic drugs are approved and safe to swap for brand-name medicines. It’s not just a list-it’s the rulebook that pharmacists, doctors, and insurers use every day to decide what you can get at the pharmacy. If you’ve ever picked up a generic pill and wondered if it’s really the same as the brand, the Orange Book is why you can trust it.

What Exactly Is the FDA Orange Book?

The official name is Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations, but everyone calls it the Orange Book because of its orange cover. It’s been around since 1984, when Congress passed the Hatch-Waxman Act. That law was meant to do two things: let generic drugs enter the market faster, and still protect the patents of brand-name companies. The Orange Book is how the FDA makes that balance work.

It doesn’t list every drug ever made. It only includes drugs that have been approved by the FDA as safe and effective. As of 2023, it covers over 16,000 drug products-both prescription and over-the-counter. About 90% of all prescriptions in the U.S. are filled with generics, and nearly all of those are tracked here.

How Do Generic Drugs Get Listed?

Generic drug makers don’t start from scratch. Instead of running full clinical trials like brand-name companies, they submit an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA). The key word here is abbreviated. They only need to prove one thing: that their drug works the same way in the body as the original.

That original drug is called the Reference Listed Drug (RLD). The FDA picks one brand-name version as the standard. Every generic must match it in strength, dosage form, route of administration, and-most importantly-how fast and how much of the drug gets into your bloodstream. That’s called bioequivalence.

Once the FDA approves the ANDA, the generic gets added to the Orange Book. You’ll see it listed right next to the RLD. The RLD is marked with a “Yes” in the RLD column. The generic gets a “No.” Simple.

Therapeutic Equivalence Codes: What Do the Letters Mean?

Not all generics are treated the same. The Orange Book gives each drug a Therapeutic Equivalence (TE) Code. These are one or two letters that tell you whether a generic can be swapped without worry.

- A codes mean the drug is therapeutically equivalent. You can substitute it freely. For example, a generic version of Lipitor with an “A” code is considered interchangeable with the brand.

- B codes mean there’s a problem. Maybe the drug isn’t reliably absorbed, or it’s a complex delivery system like an inhaler. These aren’t automatically interchangeable. Pharmacists might need to check with your doctor before switching.

- BN codes mean it’s the only product available for that drug. No generics exist yet. That’s often because the patent is still active.

These codes matter. If you’re on a Medicaid or Medicare plan, your pharmacy might only be allowed to dispense drugs with “A” codes unless your doctor says otherwise. That’s why the Orange Book isn’t just a reference-it’s a legal tool.

What About Authorized Generics?

There’s another kind of generic you might not know about: authorized generics. These are brand-name drugs made by the same company but sold without the brand name. For example, the maker of Claritin might sell a generic version of loratadine under its own label, right alongside the branded version.

Here’s the twist: authorized generics are not listed in the Orange Book. Why? Because they’re approved under the same New Drug Application (NDA) as the brand. The FDA tracks them separately on a different list-updated quarterly-called the List of Authorized Generic Drugs. So if you see a generic that looks exactly like the brand but costs less, it’s probably an authorized generic. But you won’t find it in the Orange Book.

Patents and Exclusivity: The Hidden Rules

The Orange Book doesn’t just list drugs. It also lists patents. This is where things get complicated.

When a brand-name company gets FDA approval, they must tell the FDA which patents cover their drug. That includes patents on the chemical itself, how it’s made, or how it’s used. The FDA doesn’t decide if those patents are valid. They just publish what the company gives them.

Each patent gets a number, an expiration date, and a patent use code (like U-123). These codes tell you exactly which medical condition the patent protects. For example, a patent might cover using a drug to treat high blood pressure, but not heart failure. That’s important because generic companies can still make the drug for the unpatented use.

When a generic company files an ANDA, they have to say whether they’re challenging any of these patents. If they do, the brand-name company can sue. That triggers a 30-month clock where the FDA can’t approve the generic-even if it’s ready. This is called the “30-month stay.” It’s a legal pause, not a scientific one.

Some critics say companies abuse this system by listing dozens of weak patents-what’s called “patent thickets”-to block generics. The FDA says it’s cracking down. In 2023, they updated rules to prevent listing patents that don’t clearly cover the approved use.

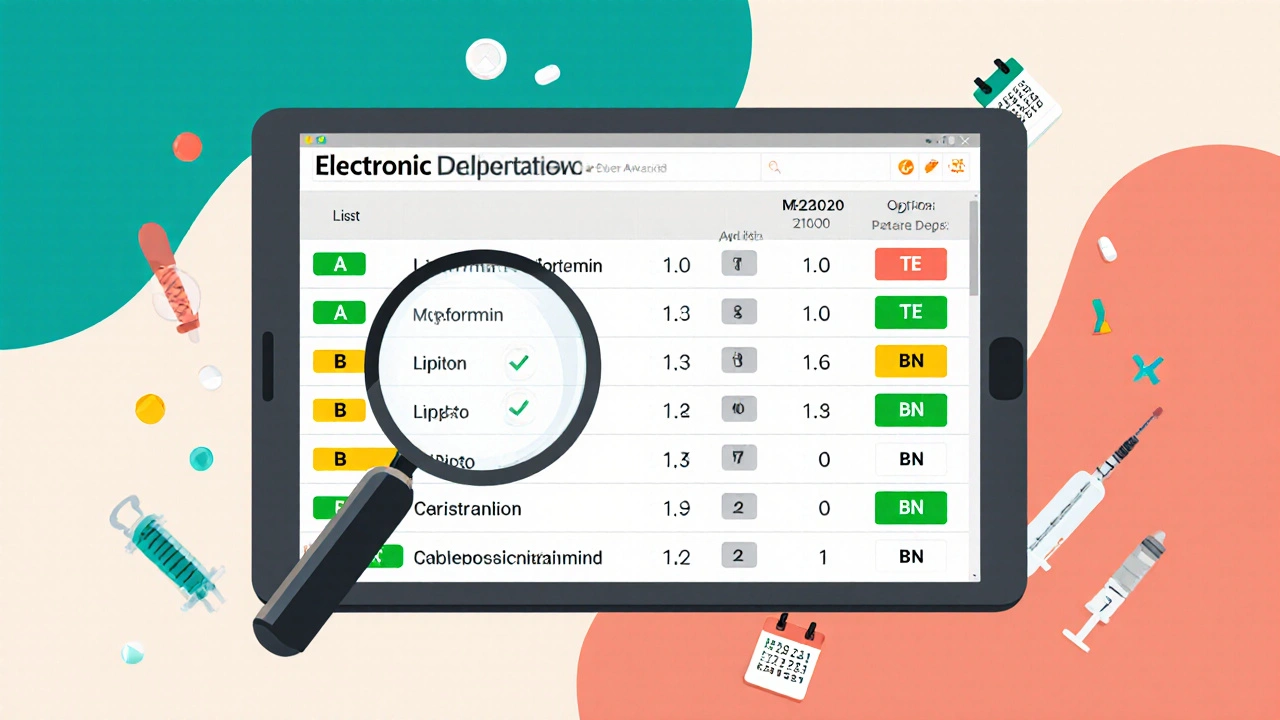

How to Use the Electronic Orange Book

The FDA keeps the Orange Book online. You can search it for free at the Electronic Orange Book website. Here’s how to find what you need:

- Search by active ingredient (like “metformin”) to see all drugs with that component.

- Or search by proprietary name (like “Glucophage”) to find the brand and all its generics.

- Look at the dosage form and route (e.g., tablet, oral) to narrow results.

- Check the TE code and RLD column to see which ones are interchangeable.

- Scroll down to the patent section to see if any are still active.

It’s not always easy. Combination drugs-like those with three active ingredients-can be messy. One pharmacist on a forum said searching for Trelegy Ellipta took 20 minutes because the system didn’t group the ingredients intuitively.

Why This Matters to You

If you’re taking a generic drug, the Orange Book is why you’re paying less. It’s why your insurance lets you switch from brand to generic without extra cost. It’s why your pharmacist can legally give you a different pill that works the same.

But it’s also why sometimes you get a different generic than last time. If the first one has a “B” code, your pharmacy might switch to another with an “A” code. Or if a patent expires, a new generic might hit the market and replace the old one.

For people on tight budgets, the Orange Book is a lifeline. A 2023 Congressional Budget Office report found that when multiple generics are available (thanks to “A” codes), prices drop 18-22% compared to single-source drugs. That’s hundreds of dollars a year for chronic conditions like diabetes or high cholesterol.

What’s Changing in 2025?

The FDA is working on a new version called the Digital Orange Book. It’s supposed to be faster, more accurate, and updated in real time-not just monthly. The goal is to make it easier for pharmacies, hospitals, and even apps to pull data directly into their systems.

They’re also testing more detailed therapeutic equivalence ratings for tricky drugs like inhalers, eye drops, and topical creams. These aren’t simple pills. The way they’re delivered can affect how well they work. Right now, the Orange Book treats them like tablets. That’s changing.

The bottom line? The Orange Book isn’t going away. It’s evolving. And it’s still the most important tool we have for making sure generic drugs are safe, effective, and affordable.

Is the FDA Orange Book the same as Drugs@FDA?

No. Drugs@FDA shows all drug applications, including those still under review. The Orange Book only lists drugs that have been fully approved and are on the market. A drug might appear in Drugs@FDA with a tentative approval but won’t show up in the Orange Book until it’s final.

Can I trust every generic drug listed in the Orange Book?

Yes-if it has an “A” code. The FDA requires strict bioequivalence testing before approving any generic. If a drug has an “A” code, it’s been proven to work the same way in your body as the brand. “B” codes mean caution is needed, often because of delivery method or absorption issues. Always check the code before assuming interchangeability.

Why does my pharmacy sometimes give me a different generic than last month?

Because more than one generic might be approved for the same drug. If your insurance or state law allows substitution, the pharmacy can switch to whichever generic is cheapest or easiest to get. As long as the TE code is “A,” it’s legally and medically acceptable. The Orange Book shows all approved versions, so your pharmacist can pick from the list.

Do over-the-counter (OTC) drugs appear in the Orange Book?

Yes, but they’re not evaluated for therapeutic equivalence. The Orange Book includes OTC drugs in a separate section, but since they don’t require a prescription, there’s no formal “substitution” system. You won’t see TE codes for them. The FDA doesn’t regulate OTC interchangeability the same way as prescription drugs.

How often is the Orange Book updated?

The FDA updates the Electronic Orange Book monthly, usually on the first business day of the month. New approvals, patent changes, and discontinued products are added then. If a drug is approved on November 15, it typically appears in the December update. There’s a delay-so don’t expect instant updates.

What’s the difference between the Orange Book and the Purple Book?

The Orange Book covers small-molecule drugs-like pills and injections made from chemicals. The Purple Book covers biological products-like insulin, vaccines, and cancer drugs made from living cells. They’re two different systems. The Purple Book was created in 2009 for biosimilars, which are like generics for biologics. They’re not interchangeable in the same way, and the rules are more complex.

Can a generic drug be pulled from the Orange Book?

Yes. If a drug is discontinued by the manufacturer, or if the FDA revokes approval due to safety or manufacturing issues, it moves to the Discontinued Drug Product List. Once there, it’s no longer considered available for substitution. You’ll see it in the Orange Book but with no RLD or TE code.

Darragh McNulty November 21, 2025

This is such a game-changer for people trying to save money on meds! 🙌 I used to freak out when my pharmacy switched my generic, but now I just check the Orange Book and chill. A code = no worries. 🤓💊

Sandi Moon November 21, 2025

One must wonder, however, whether the FDA’s so-called 'therapeutic equivalence' is anything more than a politically expedient fiction. The bioequivalence standards are laughably lenient-particularly for drugs with narrow therapeutic windows. One cannot help but suspect that this is less about patient safety and more about corporate cost-cutting dressed in regulatory finery.

Kartik Singhal November 22, 2025

A codes? Pfft. 😒 I’ve had generics that made me feel like I was on a different drug entirely. The FDA’s 'bioequivalence' is just a fancy way of saying 'close enough for government work.' And don’t get me started on authorized generics-they’re the real deal, but they hide in plain sight. 🤫 #PharmaShenanigans

Logan Romine November 24, 2025

So let me get this straight… we’ve built an entire healthcare infrastructure around a book that’s literally orange? 🤔 The entire system is a performance art piece. We’re all just actors in a play called 'Medication Theater.' The TE codes? Just the script. The patents? The stage props. And the patients? The audience who forgot they had tickets.

Chris Vere November 25, 2025

The Orange Book is a quiet hero in the background of American healthcare. It allows access without compromising safety. Many do not appreciate this balance. It is not perfect but it is necessary. The system works because it is transparent. That is rare in medicine

Pravin Manani November 26, 2025

Bioequivalence is a pharmacokinetic construct, but in practice, inter-individual variability in Cmax and AUC can lead to clinically significant divergence, especially with narrow-therapeutic-index agents like warfarin or levothyroxine. The current TE coding framework doesn't account for CYP450 polymorphisms or GI motility differences. We need a stratified equivalence model, not a binary A/B system.

Mark Kahn November 27, 2025

Love this breakdown! Seriously, if you’ve ever been confused about why your generic looks different or costs less, this is the cheat sheet you didn’t know you needed. 🙏 Bookmark it. Share it. Your wallet will thank you!

Leo Tamisch November 27, 2025

Ah yes, the Orange Book. The only government document that looks like a fruit salad and somehow dictates whether your thyroid medication works. 🍊 It’s not a database-it’s a religious text for pharmacists. And yet we trust it more than our own doctors. 🤷♂️ #PharmaCult

Daisy L November 29, 2025

I’m so sick of this! The FDA lets these cheap knockoffs in, and then we wonder why people get sick! It’s not the same! It’s not! And don’t even get me started on the Chinese factories making these pills-do you know what’s in them?!?!?! We need to BAN this nonsense! AMERICA FIRST! 🇺🇸💥

Anne Nylander November 29, 2025

OMG this is so helpful!! I had no idea about TE codes!! I thought all generics were the same!! Now I know to check before I pick up my pills!! Thanks for explaing!! 😊❤️

Franck Emma November 30, 2025

I took a generic for my blood pressure last year. I nearly died. The Orange Book lied.

Noah Fitzsimmons December 2, 2025

You people are so naive. The FDA doesn’t care about you. They’re owned by Big Pharma. The Orange Book? A distraction. The real list is behind a paywall. The 'A' codes? Just marketing. You think your insulin is safe? You’re just lucky you haven’t been poisoned yet.

Eliza Oakes December 3, 2025

Oh please. The Orange Book is a joke. I’ve had five different generics for the same drug-each one made me feel like a zombie, then a maniac, then a ghost. The FDA is just trying to sell you on the illusion of choice. Wake up. It’s all the same factory. The orange cover is just a glittery lie.

Clifford Temple December 4, 2025

I don’t care what the Orange Book says. If it’s not made in America, it shouldn’t be in my body. This is why our veterans are getting sick. Foreign generics. Foreign factories. Foreign control. This isn’t healthcare-it’s surrender.

Corra Hathaway December 5, 2025

Okay but can we talk about how amazing it is that we have a system that lets people afford life-saving meds? 🙏 The Orange Book isn’t perfect, but it’s the reason my mom can take her diabetes pills without choosing between food and medicine. Let’s not trash it-let’s fix it, together! 💪🌈